App Store Year Four: Subscriptions, iCloud offer fantastic new services... and controversies

The time between the developer preview for iOS 4 and iOS 5 was the longest to date. Rather than a spring event like in previous years, Apple didn't reveal any details of iOS 5 until WWDC 2011 in June. Also, rather than a summer release, general availability was held off until October of that year. So what did Apple manage to achieve with those extra months? Several things that weren't made available to developers, including Siri and Notification Center widgets. iCloud, however, and the sync services that came with it, were big. As was Newsstand and its subscription services, at least potentially. In keeping with tradition, however, neither was without controversy.

Meanwhile, over 500,000 apps were available in the App Store and downloads had topped 18 billion. By January, 2012, over $4 billion had been paid out to developers. By March, App Store downloads hit 25 billion, and by June, the App Store was available in 155 countries.

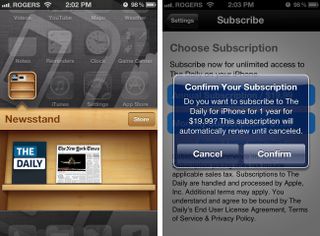

Subscription perdition

Apple originally announced App Store subscriptions in 2008 as part of the iPhone OS 3 event, but they never took off. At a special event in February of 2011, Apple's Eddy Cue joined FOX's Rupert Murdoch to announce proper subscription support on the App Store, and the Daily, a new, all-iPad magazine to spearhead it.

At WWDC in June, Apple showed off Newsstand, a special kind of folder that housed all the magazine, newspaper, and other subscription, periodical apps. Again, developers had to update to support Newsstand and its subscription features, but once they did:

- The subscription app would download to Newsstand, not the general Home screen

- The subscription app would "wake up" once a day to refresh content, if anything new was available.

- The subscription app would show the latest cover or front page artwork, instead of the app artwork, to visually cue users to potentially new content.

Reaction to the Daily was so-so. Reaction to Apple wanting their traditional 30-percent cut of revenue from subscribers, but not allowing any surcharging in the App Store to make up the difference, was explosive. The late Steve Jobs framed his position for Apple:

Our philosophy is simple—when Apple brings a new subscriber to the app, Apple earns a 30 percent share; when the publisher brings an existing or new subscriber to the app, the publisher keeps 100 percent and Apple earns nothing. All we require is that, if a publisher is making a subscription offer outside of the app, the same (or better) offer be made inside the app, so that customers can easily subscribe with one-click right in the app. We believe that this innovative subscription service will provide publishers with a brand new opportunity to expand digital access to their content onto the iPad, iPod touch and iPhone, delighting both new and existing subscribers.

The issue became conflated with digital goods being offered as in-app purchases in general, perhaps exemplified most by Amazon's Kindle App. The platform concerns that come with deviating from 30% in any way were summed up by Matt Drance, former Apple developer evangelist and current Apple Outsider:

Some say the 70/30 revenue split that accompanies IAP is too high for subscriptions, but precedent wins here. 30% to Apple across the board — app sales, IAP, and now subscriptions — is consistent, clear, and uncheatable. That cheating bit is significant: a 10% commission for subscriptions, for example, would see developers adopting the subscription system en masse so they could keep more money. Apps that were once $2.99 would suddenly be asking for installments like late-night infomercials. This would not only be a huge headache for Apple, but it would be an awful user experience. Don't expect subscriptions to deviate from a 70/30 split unless everything does.This may in fact all be red herring: the New York Times reports "Publishers say their objections are less about the steep revenue split than the lack of data." That "data" is, of course, your personal information — which they intend to monetize further in ways you probably wouldn't like very much. This is one area that I hope Apple never compromises on.

John Gruber framed it as harming middle-men in an ecosystem where Apple wanted to subsume the roll of the middle-man, and put it into the console model context on Daring Fireball:

Master your iPhone in minutes

iMore offers spot-on advice and guidance from our team of experts, with decades of Apple device experience to lean on. Learn more with iMore!

iOS isn't and never was an open computer system. It's a closed, controlled console system — more akin to Playstation or Wii or Xbox than to Mac OS X or Windows. It is, in Apple's view, a privilege to have a native iOS app.This is what galls some: Apple is doing this because they can, and no other company is in a position to do it. This is not a fear that in-app subscriptions will fail because Apple's 30 percent slice is too high, but rather that in-app subscriptions will succeed despite Apple's (in their minds) egregious profiteering. I.e. that charging what the market will bear is somehow unscrupulous. To the charge that Apple Inc. is a for-profit corporation run by staunch capitalists, I say, "Duh".If it works, Apple's 30-percent take of in-app subscriptions will prove as objectionable in the long run as the App Store itself: not very.

These issues remain, though largely below the surface today. iBooks, however, which involves similar issues of revenue split and most-favored nation pricing, is a different matter. At Amazon's behest the U.S. Justice Department has taken Apple to court and won in the early rounds. Apple has called into question the severity of the remedies sought by the DoJ and vowed to appeal.

The Daily, meanwhile, couldn't create a sustainable business, and many other periodicals simply exported iOS compatible, if not friendly, versions of their print magazines from the same workflow. It took an iOS developer, moving into publishing, to show what Newsstand and subscriptions on the App Store could really do. Marco Arment:

But just as the App Store has given software developers a great new option for accepting direct payment, Newsstand has given publishers an even bigger opportunity with subscription billing and prominent placement. Yet most publishers aren't experimenting with radical changes. They can't — to fund their huge staffs and production costs, they can't afford to deviate from yesterday's model. And most individual writers can't, won't, and shouldn't make their own Newsstand apps.

The Magazine feels like a digitally native publication, and is still running, successfully, today. It's an example of how frameworks provided by Apple can allow developers to enter into, and potentially disrupt old, less agile businesses.

iCloud sync or swim

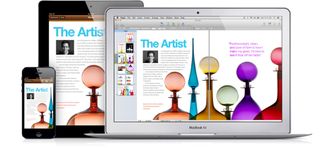

iCloud rebooted Apple's troubled and tarnished MobileMe service, rebranding the personal information management portion, taking away iDisk but giving backup and restore. For developers, however, it provided key value and document sync - or, as Apple repeated over and over again, storage up on the cloud and push down to devices.

Rather than the typical model of a single truth store with the web as the canonical view of that truth, Apple made all devices peers, including the Mac, which was placed on the same level as the iPhone, iPad, and iPod. And all copies, of all data, on all devices, were considered equal. Or, at least, the way in which iCloud handled updates and conflicts was kept completely hidden from the end user.

This proved to be both the best and worst of worlds for developers, because when it worked out, it allowed almost magical sync that required no new accounts or setup for users. When it din't work, however, it was black box that provided no mechanisms for troubleshooting.

In April of 2012, six months in, Federico Viticci surveyed developers and shared their opinions on MacStories:

The past six months have also shown that, without proper developer tools and a clear explanation of how things work in backend, things don't "just work" — in fact, quite the opposite: some developers have given up entirely on building iCloud apps for now, others are wishing for new APIs that would make the platform suitable to their needs, while the ones who did implement iCloud in their apps are torn better the positive feedback of "it just works" users, and the frustration of those struggling to keep their data in sync on a daily basis.Still, there's no question that what Apple has been doing with iCloud is nurturing a profound change in the way we think of our devices and apps as one big, connected ecosystem. With iCloud, Apple has democratized cloud sync and brought it to the masses of users and developers who were forced to switch between technologies that aren't nearly as integrated as iCloud is on a system level. The third-party apps that are solely based on iCloud still aren't that many — and admittedly Apple could do a better job at promoting those that have been experimenting with iCloud — but there's no doubt iCloud is promising in the long-term benefits it aims to achieve.

While key value sync apparently worked well enough, it only worked for very small amounts of data. Document sync took longer to solidify, but Apple's use of it in products like iWork forced them to get it done. Core Data sync, introduced later, and barely used by Apple, has been extremely painful for developers, to the point where many, publicly, stopped using it. Daniel Pasco of Black Pixel:

At the time, the option that seemed to make the most sense was to embrace iCloud and Core Data as the new sync solution of choice. We spent a considerable amount of time on this effort, but iCloud and Core Data syncing had issues that we simply could not resolve.

Either way, iCloud has not yet lived up to its promise. It's not become ubiquitous. To this day, not all apps use it, and certainly not all games Angry Birds developer Rovio recently chose to roll their own sync. Part of the reason for that is lack of cross-platform support, which means developers who also have Android or Windows apps can't use it. Brent Simmons of NetNewsWire fame writing on Inessential:

Here's the thing: half the mobile revolution is about designing and building apps for smartphones and tablets.The other half is about writing the web services that power those apps.How comfortable are you with outsourcing half your app to another company? The answer should be: not at all comfortable.

The flip-side to that is developers who would, on their own, be unable to write web and sync services, but get them "for free" with iCloud. If they're happy to stay in Apple's ecosystem, then they and their users enjoy tremendous additional functionality at far less effort and cost.

More recently, at WWDC 2013, Apple apparently addressed concerns over iCloud sync in general, and Core Data sync in particular. We'll have to wait and see how, post-iOS 7, that manifests.

In the meantime, these types of services are absolutely the future so it behooves Apple to pour every resource at their disposal into nailing them.

And so the story of the App Store continued. Amazing functionality bringing with it enormous controversy. Empowerment without transparency. Opportunity, but not without risk and frustration. Was such life?

To be continued...

- App Store Year Zero: How unsweetened web apps and unsigned code drove the iPhone to an SDK

- App Store Year One: Shocking successes, game-changers, and unpredictable pain

- App Store Year Two: Pushy new app options, iPads, and the advent of freemium

- App Store Year Three: Mild-mannered multitasking, iAD, and getting Game Center

Rene Ritchie is one of the most respected Apple analysts in the business, reaching a combined audience of over 40 million readers a month. His YouTube channel, Vector, has over 90 thousand subscribers and 14 million views and his podcasts, including Debug, have been downloaded over 20 million times. He also regularly co-hosts MacBreak Weekly for the TWiT network and co-hosted CES Live! and Talk Mobile. Based in Montreal, Rene is a former director of product marketing, web developer, and graphic designer. He's authored several books and appeared on numerous television and radio segments to discuss Apple and the technology industry. When not working, he likes to cook, grapple, and spend time with his friends and family.

Most Popular