From Colossal Cave to The Walking Dead: The legacy of Interactive Fiction

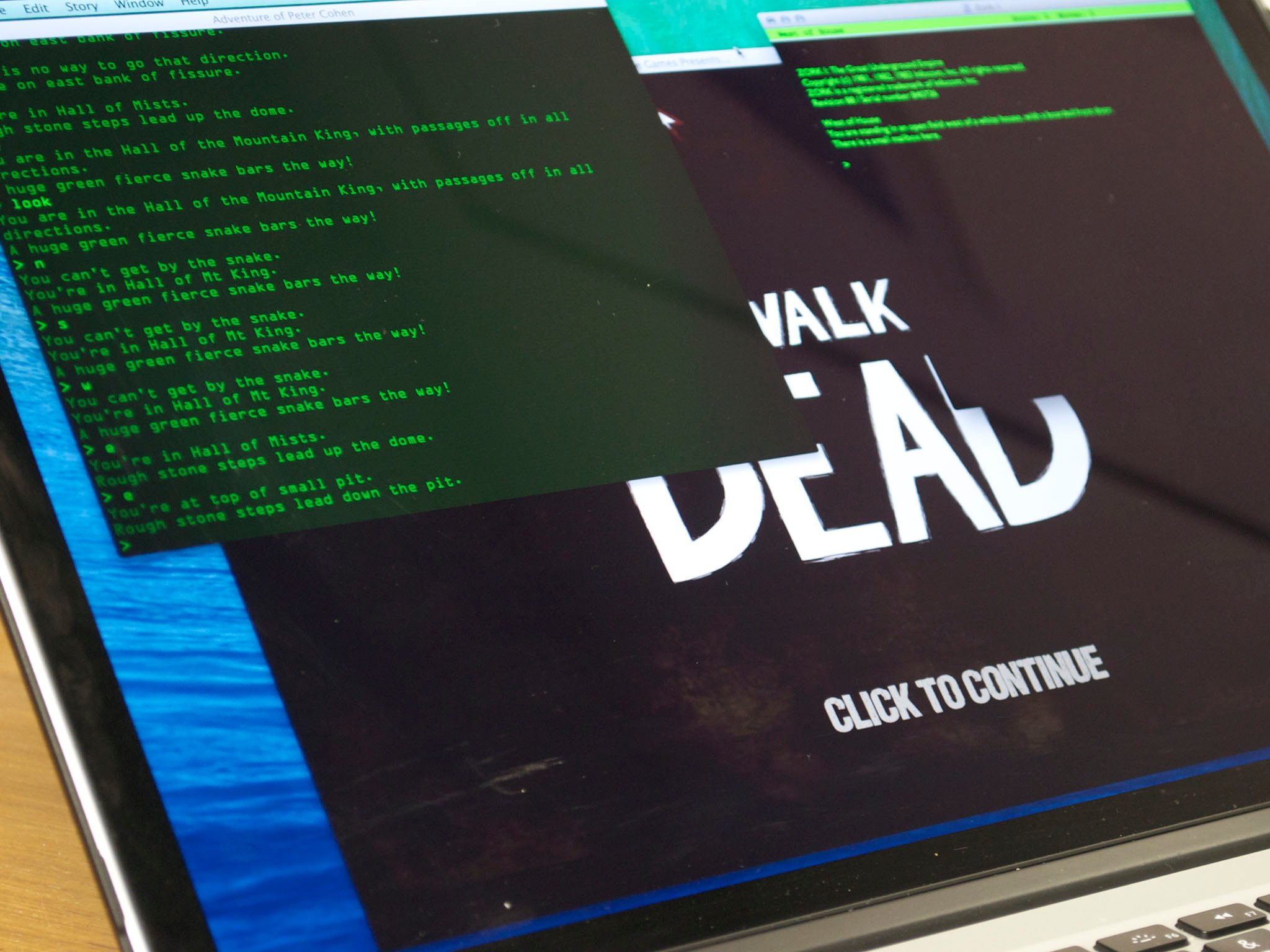

The enormously popular Walking Dead video game series can trace its lineage directly back to the dawn of video games

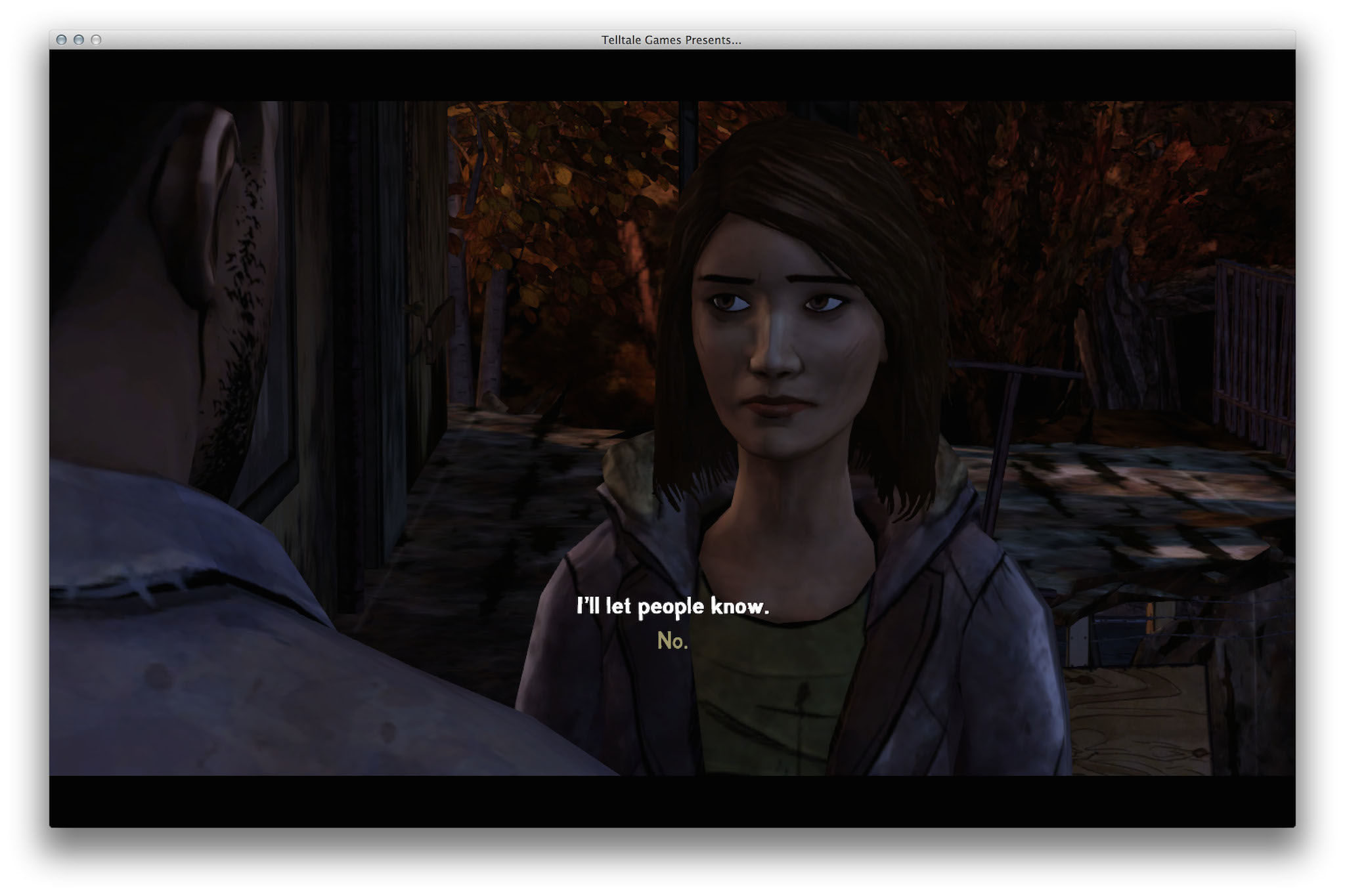

One of the best Mac and iOS game series of the past couple of years is based on The Walking Dead, the popular graphic novel and TV series. Developed by Telltale Games, it's a point and click adventure game. It's thoroughly modern, featuring top-notch voice acting, a 3D engine and great production quality. It can also trace its roots back to some of the earliest popular computer games, a genre called Interactive Fiction, or IF for short.

The beginning of text adventures

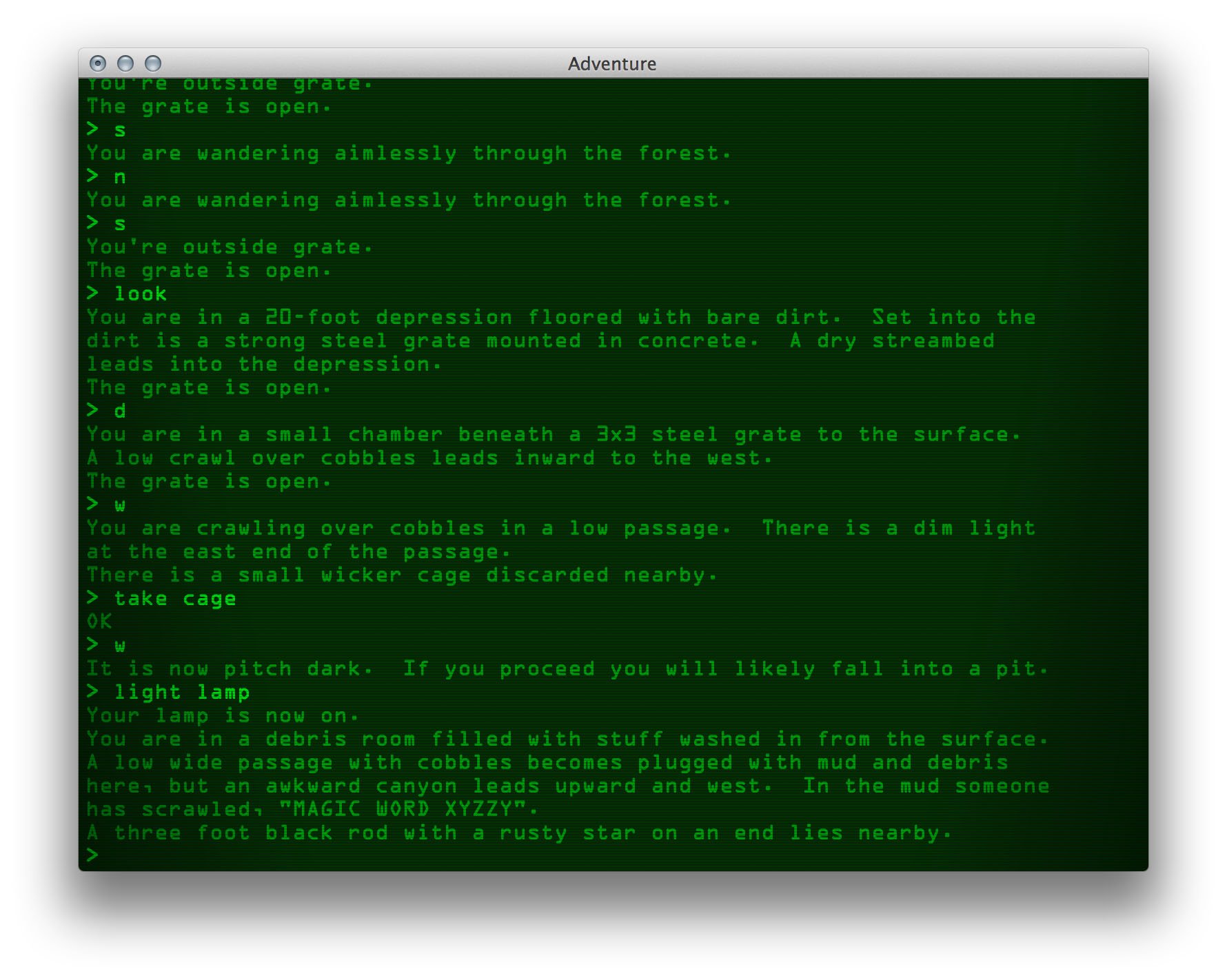

Though it certainly wasn't the first text game, the grandaddy of all these games is Colossal Cave Adventure (sometimes called simply Adventure or ADVENT in some of its incarnations), featuring an axe-throwing dwarf and a magic bridge and all manner of creative fantasy, all based on a real-world cave.

"You are standing at the edge of a road before a small brick building," the game begins. Using simple text commands you navigate your way through the world and interact.

Colossal Cave would be recreated and revamped a number of times over the years, and gave rise to a new genre of games that we know today as interactive fiction. Some gaming empires would eventually rise and fall based on the popularity of such work.

You can still play Colossal Cave — there are versions available for iOS and OS X too. (The screenshot I included is from Lobotomo Software's OS X game Adventure.)

The Infocom years

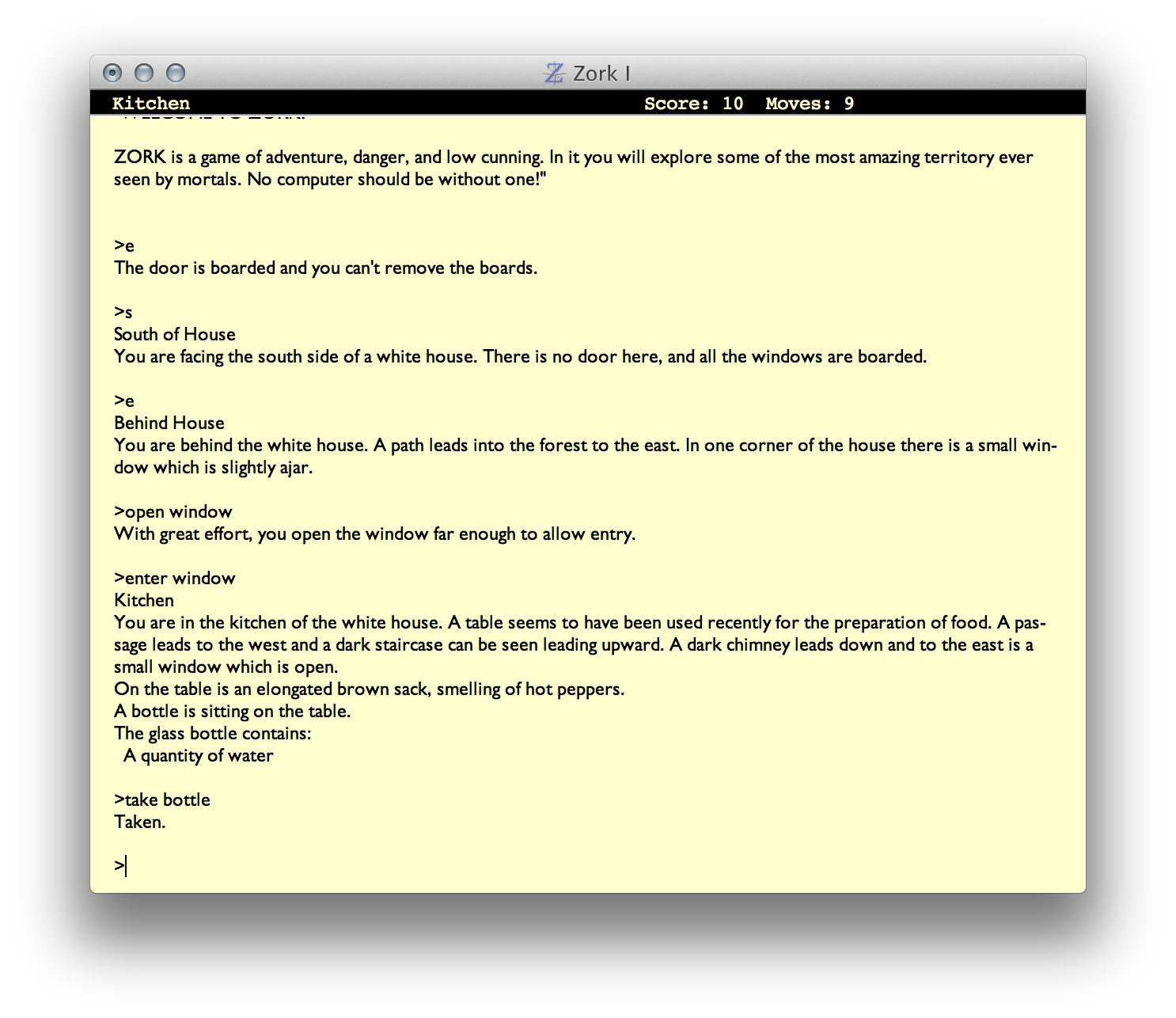

For gamers of a certain age like me, the word "Infocom" evokes memories of hours of fun. The company exploded on the burgeoning personal computer gaming scene in the early 1980s based on the success of a game called Zork, a text adventure game inspired by Colossal Cave Adventure — but vastly superior thanks to the quality of its writing and the expansion of its text parsing system, making it easier for laypeople to have fun exploring instead of struggling to understand how to enter commands.

"It is pitch black. You are likely to be eaten by a grue," was one particularly memorable (and frequent) Zork moment. And if you moved around in the dark too much without activating a light source, you indeed would be eaten by a grue.

iMore offers spot-on advice and guidance from our team of experts, with decades of Apple device experience to lean on. Learn more with iMore!

Originally developed for use on a mainframe computer at MIT, Zork would eventually be ported to almost every home computer platform available, and would spawn a number of sequels. What's more, Infocom developed an entire line of interactive text adventure games — most of them completely original works, spanning fantasy, science fiction, and more. They even collaborated with Douglas Adams to produce a text adventure game based on Hitchhikers' Guide to the Galaxy.

Infocom further sweetened the pot by producing elegant packaging for their games that often included props, which the company called "Feelies." My copy of Hitchhikers' Guide to the Galaxy included a "Don't Panic" button, "Peril Sensitive Sunglasses" (made of black cardboard) and other props, for example.

In the mid-80s Infocom was acquired by Activision. The company folded entirely in 1989, though its games live on today in the form of "Z-Machine" emulators like Andrew Hunter's Zoom for OS X.

Graphical adventure games take root

By then gamers' tastes changed to more graphical fare. Sierra Online would herald the next great revolution in text adventure games with titles like King's Quest, which employed color graphics and pseudo-3D scenes you could move your character to walk through and interact with. Text descriptions, written dialogue and narration and a text parser to enter commands still figured prominently in the game, of course. The graphics were great, but at its heart, King's Quest was still ultimately a text adventure game. (In recent years King's Quest has been resurrected by AGD Interactive, which remade the first three games in the series for Mac and Windows.)

Graphic adventure games continued to refine the way players interacted with their environment, eventually eschewing a text parser all together. LucasArts saw a lot of success in the 1990s with their graphic adventure games like Day of the Tentacle, and series like Sam & Max and Monkey Island. Westwood Studios, legendary makers of the Command & Conquer real time strategy game series, had their own success with Legend of Kyrandia.

Nowhere was the emphasis on graphics-only adventures more evident than with Myst, the groundbreaking graphic adventure game from Cyan. Originally developed on the Macintosh using Apple's HyperCard — an early graphically oriented programming tool — Myst emphasized elaborate visual puzzles and some embedded videos that were cleverly integrated into the game's graphics to move the story along. (Myst continues to live on; you can download the reworked version with a real 3D engine, RealMyst, from the iOS App Store and Mac App Store.

Myst would inspire a new generation of game developers to dabble with the graphic adventure game format — series like Presto Studios' The Journeyman Project leveraged burgeoning multimedia technology to incorporate pre-rendered 3D graphics, video and audio together into an immersive adventure game.

Graphic adventure games waxed and waned in popularity as gamers' tastes continued to evolve. Text-driven adventures, however, seemed like a dead end. They've carried on in some niche markets — Japan has, for years, had a market in "visual novels" that emphasize a text-based narrative — but it seemed like the western market was moribund.

The return of the graphic adventure game

Then Telltale Games came along.

It may not come as a surprise, but Telltale Games was founded by former LucasArts employees. They picked up where LucasArts left off. LucasArts shuttered a Sam & Max sequel that graphic adventure game fans were clamoring for, the employees left and founded Telltale. That game didn't come to fruition but Telltale would secure the rights to the Sam & Max franchise. They'd go on to acquire the rights to other licenses including Back To the Future and Jurassic Park. Telltale exploded with the release of The Walking Dead, which has proven to be enormously popular on both Mac/PC and iOS platforms.

Telltale Games' graphic adventures are the next logical step for this style of gameplay — fully 3D-rendered environments featuring scripted scenes. Taking control of the player character you can walk around and interact, setting off trigger events that require action, puzzle-solving or quick thinking to avoid death. There are also key elements of text adventure games of yore, such as branching storylines that change depending on how you handle a situation, or different choices in dialogue that affect how characters react.

Telltale's not stopping with The Walking Dead, either. They've had broad critical acclaim for The Wolf Among Us, a new episodic series based on a graphic novel series called Fables, and they just recently announced Tales from the Borderlands, based on the popular first person shooter from Gearbox Software.

Telltale isn't the only modern company producing graphic adventure games, either — Double Fine Productions, founded by another LucasArts alumnus, Tim Schafer (creator of Grim Fandango, a LucasArts graphic adventure hit), recently released Broken Age, a game whose development was paid for via a campaign on the crowdfunding site Kickstarter. There are other examples too — last year's Gone Home employs a graphic adventure narrative to tell a really unusual story for a video game — it's a coming of age story recounted as clues found by a young woman wondering where her family has gone. Device 6 for iOS deconstructs the genre even further, a combination of text, still images, videos and puzzles that immerse you into a surreal thriller.

We've come a long way from the days of pure text-based adventures, and we'll never see that level of success again. Despite the success of niche publishers like Telltale and Double Fine, the phrase "adventure game" is largely ignored in the boardrooms of video game publishers as a commercially unviable genre, compared to the vast money made by first person shooters, massively multiplayer online games and other more current fare.

IF's legacy lives on

Purely text-based interactive fiction, for its part, may no longer be a commercially viable game genre, but it's far from dead. The Interactive Fiction Database is a game catalog that offers visitors links to IF past and present. There's even a modern day equivalent to the Choose Your Own Adventure books I mentioned — Inklewriter. This site enables you to write branching, interactive stories without having to worry about programming. The developers of Inklewriter even offer a Kindle conversion service, bringing the Choose Your Own Adventure concept back to its roots as the modern equivalent of a book.

Whether you prefer full-blown graphical adventures, text-based adventure games or Choose Your Own Adventure stories, there is still a thriving community of IF writers and players and plenty of new content to explore. Just don't expect any more Feelies any time soon.