iPad is the present and future of education for these devoted teachers

iMore offers spot-on advice and guidance from our team of experts, with decades of Apple device experience to lean on. Learn more with iMore!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Like most of us, I haven't had an in-person meeting in nearly a year. I haven't shaken anyone's hand in that long, either. The ways we communicate and learn, the ways we connect with other people in general, have been so disrupted, so irretrievably altered, that it's hard to see a way back to pre-Covid times.

In the education space, this disruption almost seems like a fork in the road. Do we continue as we were, or do we try forging a new path that not only leans on technology but sees it as a primary and necessary part of learning? School boards have embraced iPads and Chromebooks as tools in recent years, but some see them as extensions of, not replacements for, existing book-and-pencil taxonomy, an augmentation of an existing practice.

The future of education

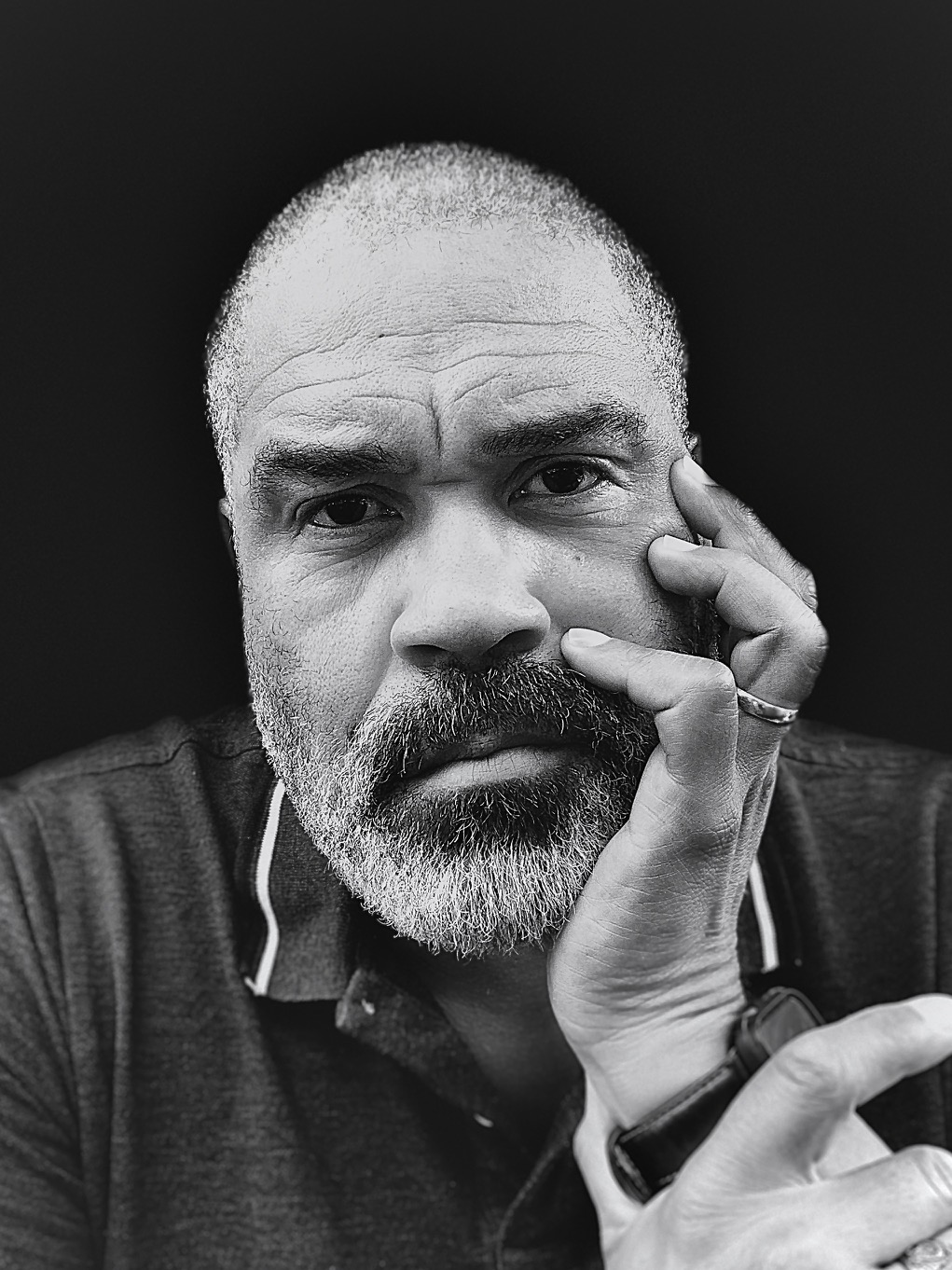

Dwayne Matthews doesn't see it this way. A former teacher at Toronto's biggest school board, he now positions himself as an advocate and evangelist for technology integration within education. I spoke to him earlier this month about how the future of education in schools needs to focus less of substituting books for tablets and laptops, and should embrace how the internet can drastically modify, augment and ultimately transform the way people learn.

Article continues belowMatthews is an Apple evangelist and looks at things through an iPad-centric lens (and full disclosure, our conversation was set up but in no way mediated by Apple's PR department), but he talks in generalities about how technologies like digital pen input and augmented reality can, and eventually will, keep kids engaged both in-class and in at-home environments.

"In Toronto, most schools are still talking about substitution," he says, which leads to a one-to-one replacement. But Matthews is looking forward to a time when all school boards are approaching digital education as the primary choice — the only option. His eventual goal is to provide individual education learning plans, or IEPs, that are catered to each student in a class.

Simultaneous learning that's done individually or in small groups, with technology at the center, is how he sees things progressing. "Personalized devices lead to personalized educations," and there's evidence to show that students are perfectly capable to adapt to learning through tools, like iPads, that they've already mastered.

It's a problem of scale, too — creating and executing individual lesson plans is difficult when everyone has to use the same source texts. But adjusting the plan to include app or augmented reality experiences should be easier, especially if they meet the criteria set forth by the school boards. He also points to the improvement in iPad capabilities and durability of the past few years. The cheapest iPad, which starts at $329 (though less for schools and educators), is not only much faster than it was half a decade ago, but it can withstand more wear and tear and supports stylus input through Apple Pencil.

iMore offers spot-on advice and guidance from our team of experts, with decades of Apple device experience to lean on. Learn more with iMore!

"Kids expect a certain amount of speed in their learning," Matthews says, because they're used to taking in so much information quickly through various screens. Instead of limiting screen time and finding ways to slow them down, he suggests schools embrace the frenetic nature of these portable devices and curate experiences that are going to lead to healthy long-term relationships with these devices, instead of constantly mediating their use. For most students, iPads and other pieces of technology are the main course, not the dessert.

There are obviously pitfalls to this fulsome embrace of digital learning, especially for kids who aren't able to stay focused on a single task, or even associate phones, tablets, and computers primarily with entertainment and content consumption, not education. "Apple builds in strong parental and educator controls into their products, and we have to be very careful about how much access we give them." But as long as the sandbox is the right size for the child's age and ambition — again, it comes back to IEPs — things should go well, and set the students up for the future of education, not just its present.

The disrupted present

But education's present is important because it's happening right now, in front of MacBooks and iPads on stands and well-used Chromebooks, and any other laptop that can be spared. In early February, I also had a chance to speak with David Watkins, an art teacher who came out of retirement during the pandemic to continue trying to keep kids engaged in art.

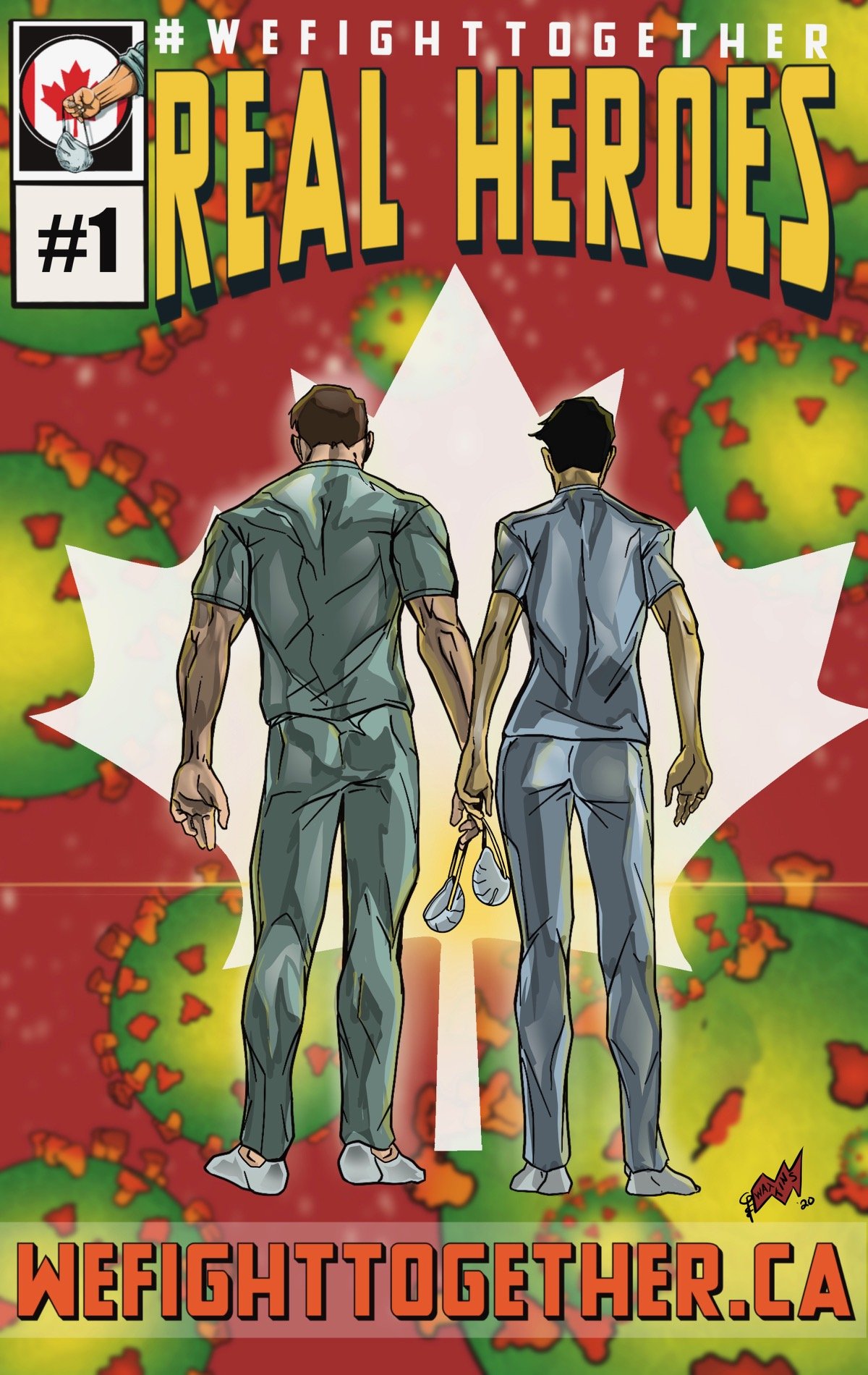

Watkins made some waves last April when he and his partner Jay Own created We Fight Together, a digital illustration campaign that highlights the work performed by frontline workers across Canada and around the world. Based on the comic books that Watkins enjoys, and draws himself, it provided some much-needed positivity during the early months of a very tenuous situation.

Like Matthews, Watkins believes that the iPad is the best tool for kids to learn creative tasks. He thought this when they were all in the same class learning in front of a projector, and he feels it doubly so today when most are at home sitting at kitchen tables in front of laptops. "It's just a natural fit," he says, "because to engage students properly you have to use what they know."

Source: David Watkins

I'm a hopeless artist — I can't draw anything beyond a stick figure — but I've taken a couple of Zoom-based art classes over the past year and they've been surprisingly gratifying. One was done using art and canvas, and the other I chose to do using the iPad Pro and an Apple Pencil. The ability to use non-destructive layers in an app like Procreate wasn't something I thought much about until I needed to create a finished product, but being taught how to methodically and patiently build a piece of art, rather than just slap something together, made the digital equivalent feel as rewarding as the physical one.

"I used to teach art with a stylus and an iPad, but when the Apple Pencil was released it opened up a whole new world," he tells me over a virtual call. Watkins has the perfect demeanor for an art teacher: patient but self-assured, which are two characteristics that have likely been honed from years of interaction with stoic and moody teenagers.

Watkins teaches in parts of Toronto where he feels most needed, where school funding is comparatively low and where Covid has impacted communities the hardest. They're also the people from which he draws inspiration. "The characters I create in my own comic books are based on the kids who others don't often speak to." Through art, he says, "I want to reach those students who can't be reached in other situations.

For both men, dealing with this disruption in education has been a blessing and a curse. It's placed a spotlight on how technology is no longer optional when practically everyone is learning remotely, and it also raises the specter of how even an iPad, with its myriad ways of connecting virtually with other people, can't replace the physicality of being in the same room with friends and teachers.

But until then, an Apple Pencil and a blank slate will just have to do.

Daniel Bader is a Senior Editor at iMore, offering his Canadian analysis on Apple and its awesome products. In addition to writing and producing, Daniel regularly appears on Canadian networks CBC and CTV as a technology analyst.