Pokémon Go Fest Chicago: The fun, the failure, and the legendary

Neither the Pokémon Company, co-owned by Nintendo, Game Freak, and Creatures, nor Niantic, the developers of Pokémon Go, are strangers to events. TPC has held Pokémon events for years and Niantic has held them for its previous game, Ingress. In that light, Pokémon Go Fest Chicago was set to be the next big step for both — bringing the virtual Pokémon Go events to the real world.

Put the popularity of Pokémon together with the demands of online, though, and it becomes something else entirely. Virtual worlds open up where thousands of players on-location can work together with millions worldwide to unlock and conquer challenges. And cellular networks and gaming infrastructure can come crashing down around them.

Poké Fest dawning

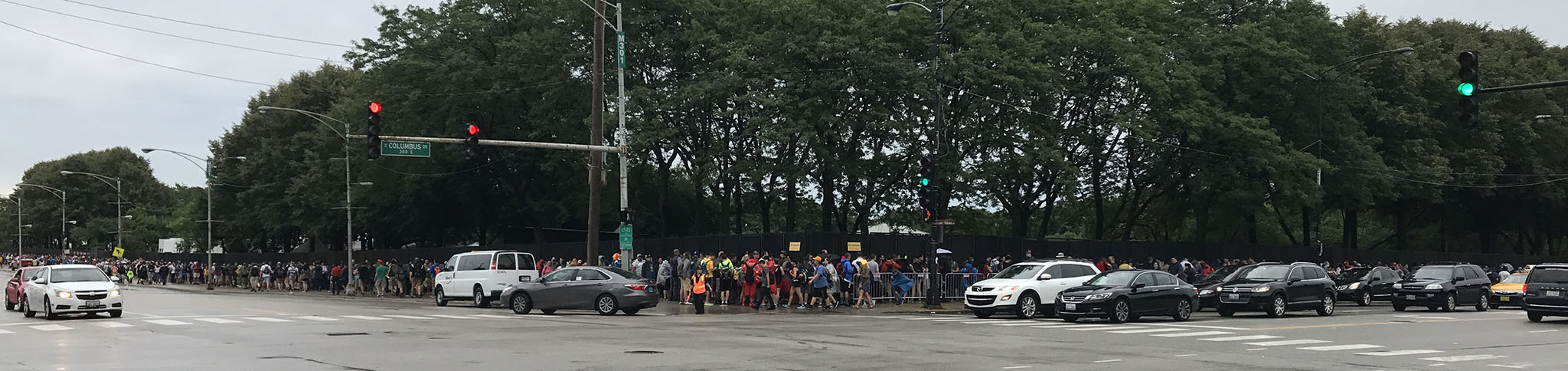

It was raining early in the morning before the venue, Chicago's Grant Park, opened. That didn't stop a line that stretched down the block, around the corner, and down several more blocks. Capacity was set at 20,000 people and it looked like almost that many had shown up. Including a couple thousand from outside the U.S.

Some of them were in full-on cosplay. Dressed as Pikachu or as their avatar, complete with top hat and shoulder Eeevee. Many more were wearing their team colors and logos — the red firebird of Valor, blue icebird of Mystic, or yellow lightning bird of Instict. Men, women, and entire families were all there, eager for the event to start.

There was a clever system in place to prevent "spoofers" — people who fake their GPS coordinates to play the game in locations in which they're not actually physically present — from exploiting the event. Every attendee got a QR code that had to be scanned in in order to activate the event badge and unlock all the event content.

I got there early for the media briefing, where Niantic CEO John Hanke spoke briefly before the event began.

#PokemonGOFest John Hanke speaks! pic.twitter.com/Sm4T6vS026#PokemonGOFest John Hanke speaks! pic.twitter.com/Sm4T6vS026— Rene Ritchie (@reneritchie) July 22, 2017

At Google, Hanke led the Geo Team that built critical technologies like Google Maps and Google Earth, and then spun Niantic out to work on next-generation geo-location gaming with Ingress and, now, Pokémon Go. He's a legend in the industry. And one that seems to take delight in seeing people engage with the technology he and his team have built.

Master your iPhone in minutes

iMore offers spot-on advice and guidance from our team of experts, with decades of Apple device experience to lean on. Learn more with iMore!

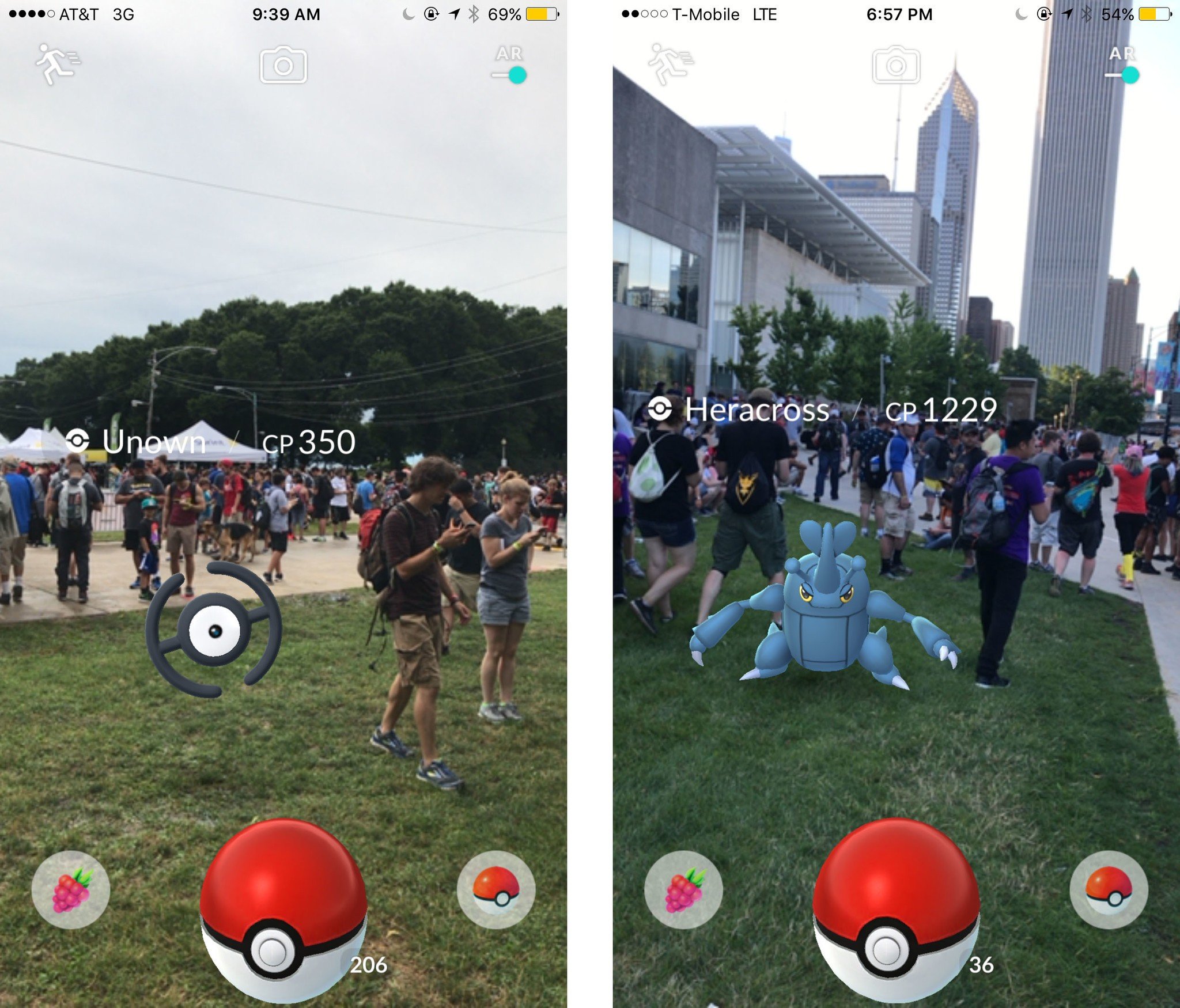

Once Hanke finished speaking we were encouraged to join in on the festivities. That included catching the "rare" Pokémon assigned to the event: Heracross, which is usually region-restricted to southern Florida and South America, and Unown, a Pokémon that can assume the 26 shapes of the alphabet. (Fittingly, C, H, I, A, G, and O were the ones made available for the event.)

When a Heracross or Unown would spawn, you'd hear people yell out and then see a massive swarm descend on the area to try to catch it. No shoving, no pushing, no rudeness or lack of concern for other players. Even in all the excitement it was a clear expression of a community coming together and helping each other.

The same was true when the Raids started. They were done differently than usual — and it turns out where an example of how Raids would work after the event. Instead of an Egg appearing with a countdown timer and then, when the timer ended, hatching into a Raid Boss, the Raid Boss appeared immediately, ready to battle. And several of the same Raid Bosses appeared closely together at the same time so everyone there could have a chance at a Snorlax, Tyranitar, or Lapras.

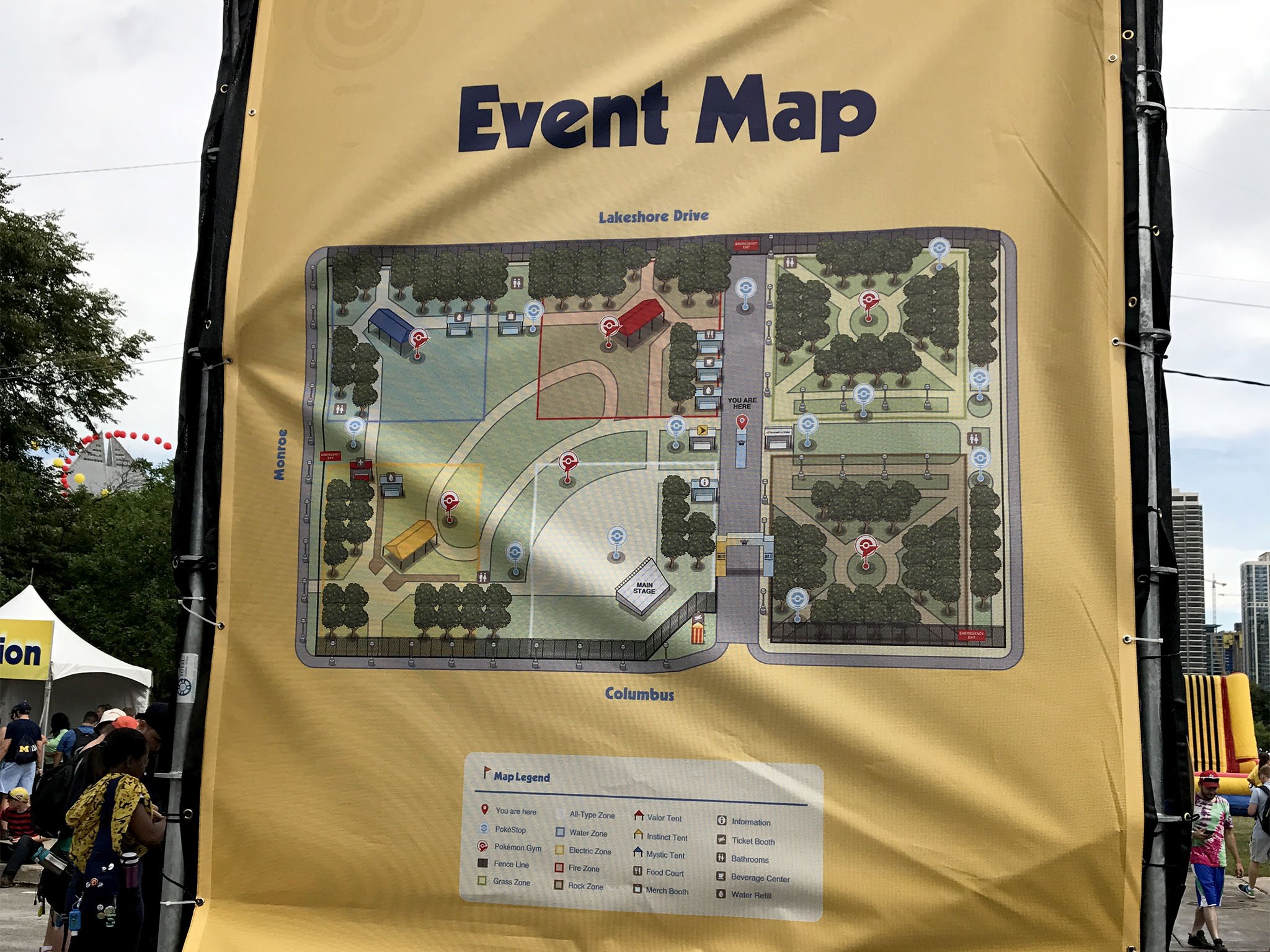

The setup was fun as well. There was a large center stage area ringed with real-life replicas of Poké Stops, big, color-coded tents to serve as lounges of the three teams, and water station, a Pikachu photo op, a merchandize stand, and a concession area that offered hotdogs, pizza, Chinese buns, and other food.

Signs were also up connoting areas of each of the Pokémon "types" — grass, fire, earth, etc. — that would play into the challenges later.

There were some odd choices up front. You could buy official Team T-Shirts at the merchandize store, for example, but not the event shirt. There were only a few of those, as we'd discover later, and they had to be won. Next time it'd be great to see the event shirt available for purchase and a special achievement shirt given away as a prize.

But that was a small thing, at least compared to what came next.

Carrier crashes and server meltdowns

Pokémon Go Fest took up a section of Grant Park roughly one quarter of the size Lalapalooza occupies. That led the cellular networks, namely AT&T, Verizon, Sprint, and T-Mobile, to assume the millions of dollars of towers, repeaters, and other infrastructure they'd already invested in the park would be more than enough to handle the much smaller crowd assembled for Pokémon Go Fest.

They were, to put it mildly, wrong.

Lalapalooza may cover four times the space and host four or more times the people, but those people aren't hitting the networks as hard and as always as Pokémon Go players. It's like a city street that typically handles a few hundred commuters thinking it can host the Grand Prix. Suddenly the smallest problem becomes a crash-level event ready to happen.

AT&T, Verizon, and Sprint went down early and hard. T-Mobile maintained a few small pockets of service, but not much more.

That mean thousands of people couldn't connect. Worse, those who could soon found Ninatic's servers crashing as well. The game wouldn't load. If it did, in-game elements wouldn't appear. If they did, the game froze when you tried to interact with them. If they didn't, you crashed anyway.

It wasn't everybody and it wasn't all the time. Thousands of people still managed to play for short spurts, some even with relative normalcy. Many didn't though, and as the day grew hotter, they grew more and more frustrated.

It was even worse outside where it was taking forever to get everyone from the lines into the event. There simply weren't enough entrances or enough capacity to handle the crowd.

"We can't play!" "We can't play!"

That was the chant that interrupted and eventually ended Pokémon Go's first big presentation on the stage. Thousands of people, gathered under the blazing sun, unable to connect to the network or the game, voicing the anger and powerlessness they felt at being shut out of the event they'd paid and, in some cases, traveled so far to attend.

To their credit, both the networks and Niantic went into crisis management mode immediately. The networks tried to point more resources and repeaters at the venue, and Niantic tried to figure out what was causing the in-game issues. They even turned off things like in-game animations for Lures.

John Hanke didn't hide from any of it either. He'd settled down next to the stage to talk with players and sign autographs, and he stayed doing just that. Even when he was booed and jeered for the issues, he stayed put, for hours and hours, engaging with the people at the event. That was incredibly impressive.

#PokemonGOFest @johnhanke is *still* meeting and greeting. #ironmanhttps://t.co/zR0OrcABMN pic.twitter.com/lk6frXEkka#PokemonGOFest @johnhanke is *still* meeting and greeting. #ironmanhttps://t.co/zR0OrcABMN pic.twitter.com/lk6frXEkka— Rene Ritchie (@reneritchie) July 22, 2017

By around 1 p.m. CDT everyone was into the event and, while a few small improvements were made, and some people were able to play, many still were not.

Mike Quigley, Niantic's chief marketing officer, soon took the stage to apologize for the issues, update everyone on what was being done, and tell people what the company was going to do to make it up to them.

#PokemonGOFest Niantic talks refunds, coins for attendees. pic.twitter.com/zSf2gHxnCx#PokemonGOFest Niantic talks refunds, coins for attendees. pic.twitter.com/zSf2gHxnCx— Rene Ritchie (@reneritchie) July 22, 2017

#PokemonGOFest Details of the 2 mile radius extension for rare spawns. pic.twitter.com/2KBv6dus8t#PokemonGOFest Details of the 2 mile radius extension for rare spawns. pic.twitter.com/2KBv6dus8t— Rene Ritchie (@reneritchie) July 22, 2017

Everyone registered for the event would be given a refund for the price of the ticket. Everyone would be credited $100 in in-game coins. And the "rare" spawns would be extended for a 2-mile radius around Grant Park in hopes people would go out and keep playing, reducing the congestion at the venue, and allowing them to get some successful game time in.

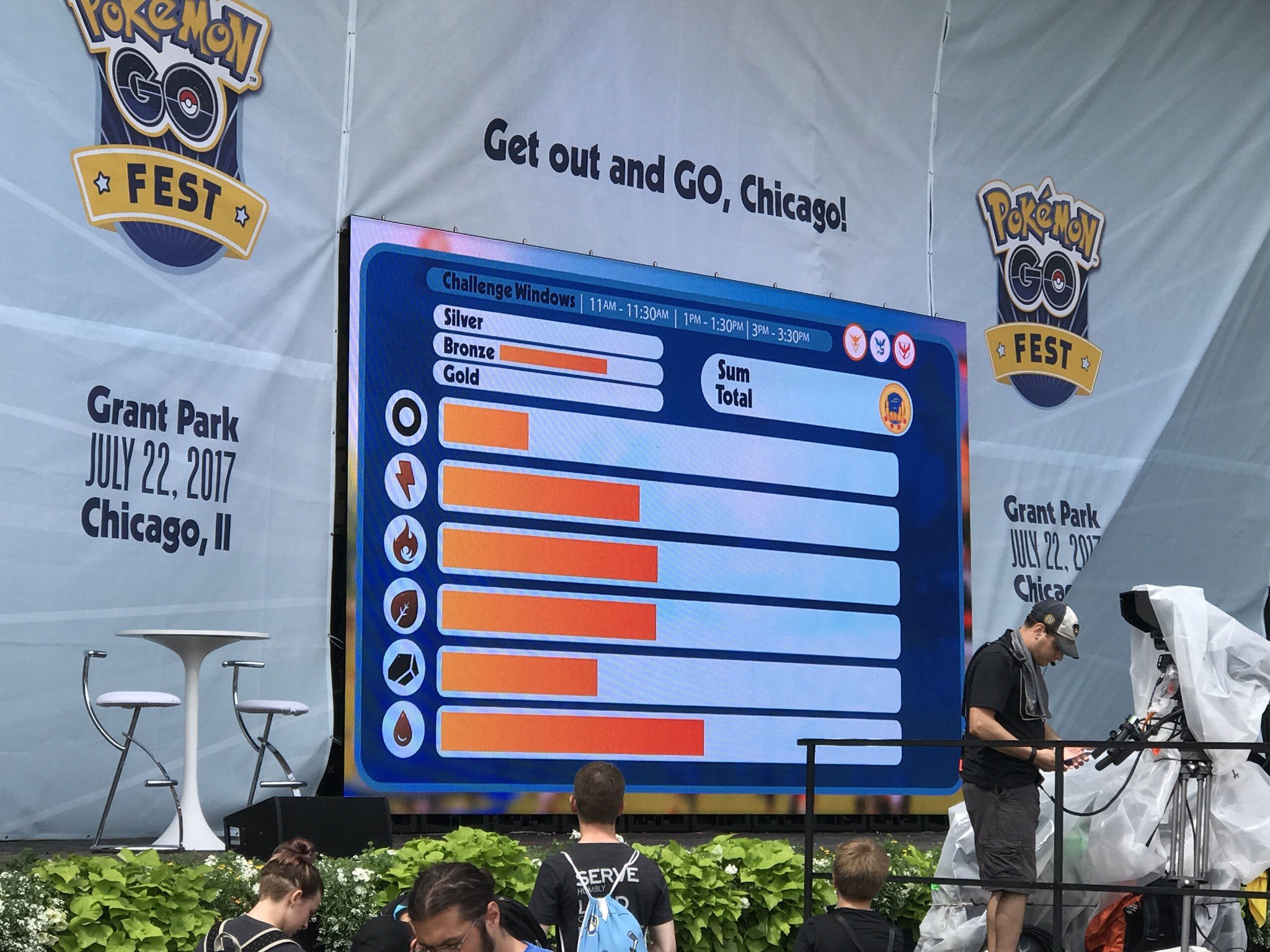

The challenges

The plan for the event was complex and, perhaps, confusing from the start. The thousands of players at the event would catch Pokémon of different types to unlock different kinds of bonuses. The millions of players around the world would then catch as many Pokémon as they could to extend those bonuses for a day or two, and unlock a "mystery challenge" back in Chicago. If that mystery challenge was successfully completed in Chicago, it would be unlocked for everyone around the world.

There'd be a few "windows" for the challenges, which seemed to be the part that most confused people, and everything would come to a head at the end of the event.

The mystery challenge was widely expected to be the release of the first Legendary Pokémon, something that'd been teased for a while and hotly anticipated since the game's launch.

Most also assumed it'd be a case of Niantic drawing a target around whatever the event managed to hit, since sending almost 20,000 people home unsatisfied to face however many million disappointed fellow players around the world would be unimaginable.

By the end of the day, though, it was less about beating the challenges and more about salvaging the event. And in that, Niantic delivered.

Every bonus was unlocked and for the maximum 48 hour window. There was no way the networks or servers could handle the original plan — the first Legendary Raid unlocked at Grant Park — so Niantic announced everyone registered for the event would be given the first Legendary, Lugia, and have it automatically added to their account.

Because the Mystic Team contributed the most, their icebird, Articuno, would be the next Legendary released, with Valor's Moltres and Instict's Zapdos to follow.

They apologized again and you could see, from executives to hosts, they were crushed. But the crowd, for the most part, left feeling heard and if not happy, at least consoled.

The real Pokémon Go Fest Chicago

That's where we all thought the story would end. Turns out, though, that's where the real Pokémon Go Fest Chicago began.

At around 8 p.m. CST, Legendary Raids started appearing. Lugia and Articuno both. All over and around the park. Word spread quickly and, soon, thousands of people were gathering to get their Legendaries.

At first, right near Grant Park, the issues continued. People couldn't log in, couldn't start the raids, or crashed during the raids. As the night went on, though, and people spread out, the problems disappeared and the fun began.

There's nothing to describe what it's like seeing thousands of people, grouped by the hundreds, raiding together. It was amazing.

Everyone was orderly, polite, and helpful. We walked from raid to raid, battling in dozens of groups of 20 at a time, beating Lugia and Zapdos, and then discovering that Niantic had gifted Chicago players with one more make-good:

100% catch rate for the Legendaries.

That meant, as long as you beat the Raid Boss, you were guaranteed to catch it. Something very, very different than the 2% (up to 20% with modifiers) that was being seen outside Chicago.

I walked around until the raids ended around 10 p.m. CST, catching four Lugia and three Articuno. I'm sure others were faster and more efficient, and caught even more.

This was the Pokémon Go Fest everyone had been waiting for.

Lessons learned

Niantic claims they'll be investigating what happened, learning from it, and making sure whatever real-world events they do next don't suffer from the same problems. It was a body blow but, hopefully, it'll make everyone involved not just smarter but wiser.

It was a huge disappointment for organizers and players alike but, at the end, we got to see the very best of both. We saw a CEO and CMO that never run, never hid, but faced the crowds with compassion and grace and did the best they could to make good. And we saw thousands of players get upset but also get over it and engage in the Legendary Raids with gusto.

It was unintentional and inexcusable, and should never happen again, but it was also perhaps the best ending for the first real-life Pokémon Go event imaginable.

Rene Ritchie is one of the most respected Apple analysts in the business, reaching a combined audience of over 40 million readers a month. His YouTube channel, Vector, has over 90 thousand subscribers and 14 million views and his podcasts, including Debug, have been downloaded over 20 million times. He also regularly co-hosts MacBreak Weekly for the TWiT network and co-hosted CES Live! and Talk Mobile. Based in Montreal, Rene is a former director of product marketing, web developer, and graphic designer. He's authored several books and appeared on numerous television and radio segments to discuss Apple and the technology industry. When not working, he likes to cook, grapple, and spend time with his friends and family.